Robert Wyatt on high versus low, jazz versus pop, participants versus innovators, and Bela Bartok versus The Genius of Ray Charles:

"I thought, Genius? How could he be a genius if he's only a popular singer? Clearly a misuse of the word. I was like that. I didn't really have any argument with my Dad. I really liked my parents and I liked what they liked, the art of the 20th century, the surrealists, the dadaists and all that stuff. But with Ray Charles, it was a difficult moment because as far as I can hear, bearing in mind my caveats, Ray Charles singing a ballad, even a soppy one like "Don't Let the Sun Catch You Crying", is as good as Bartok's Violin Concerto or Miles Davis. I knew it was a slushy pop song, just a tune with tinkly cocktail piano, and because it had violins on it, it didn't have any jazz cred. I couldn't even work out what the words were half the time, but I thought, it's an astonishing record, absolutely beautiful. Suddenly any idea of a hierachy of art crumbled away in my mind, and as far as I was concerned, there was no intrinsically superior idiom.

...Later, when I was making music myself, it was a bit embarrassing because we (Soft Machine) weren't playing regular pop music. people said, "This is better than pop music, it is superior." Once again, I could see incipient hierarchies reemerging, like there was this need to have them.

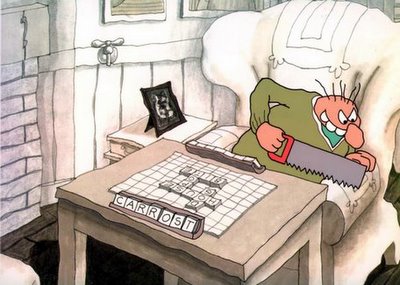

...Even so, I hadn't yet finished with hierarchies myself. Before buying a record, which wasn't very often in those days, I went on and on subdividing jazz into participants and innovators and geniuses and not-geniuses. All right, we got geniuses here: Thelonius Monk, yes; Charlie Mingus, yeah; Charlie Parker, yeah, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, yes... Ornette Coleman, can I buy Ornette Coleman? Well, OK, for the tunes, yeah?

Of course, I was missing the main event, which was hundreds and hundreds of people playing music and having a fantastic time doing it, out of which come some people with a few diamonds. But genius is in the whole culture, fermenting away in hundreds of different ways and every participant is part of it."