Robert Frank

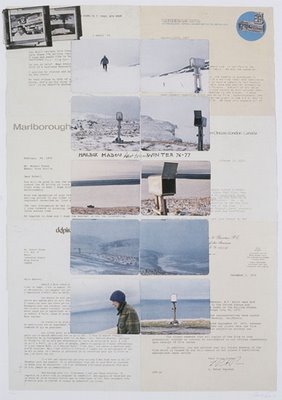

Robert FrankCollage Suite, 1980.

One of 6.

At the Equinox Gallery until Nov. 25th.

Robert Frank's late work seems to be barely tolerated by a lot of artworld folks, most of whom can't seem to reconcile the visionary milestone that was The Americans with the sloppy, embarrassingly personal films and photo-works that have dominated his output ever since.

The problem, I'm told, is twofold. Not only are the later works hopelessly retrogade in comparison with his earlier groundbreaking photographs (Rauschenberg's silkscreens having already been around for about a decade by the time Frank began cutting, painting and collaging his photographs,) but the undistilled emotionality of much of the work seems too raw, too formless to be able to inspire or sustain much critical examination; as if Frank were tearing individual pages from his diary and tacking them to the wall as art.

The subject of the film and photo-works is invariably Frank's own sense of loss. The loss of his belief in the power of photographic images, and more tangibly, the loss of his two children, Andrea and Pablo, to death and mental illness in their early twenties.

It's pieces like Andrea, 1975, in which Frank states flatly "...she was 21 years old and she lived in this house and I think of Andrea every day." that are often singled out for complaint by his critics as being too nakedly confessional.

"For an artist of public sensibility, the howl of loss needs a ceremonious consistency so that private sorrow may have a public shape..."

-W.S. Di Piero

In other words, all the private pain in the world don't add up to a drop of public art if it isn't first filtered through a recognizably formalized image, (think of those screaming fragmented figures in Guernica, or the swirling, circular unity of The Scream.) In comparison, Frank's collages seem about as fully formed as the inside of a tomato. They are too close to the center of Frank's pain for comfort.

But it's this alarming emotional proximity that accounts for their unique power (and it is unique, as any first-year art student whose tried to imitate Frank's seemingly artless approach to collage will tell you.)

There is something in the work that is simultaneously disconcerting and comforting. The very elements that make Rauschenberg's collages so much fun- the movement, the vibrancy, the swing of them- are consciously and deliberately absent from Frank's images. In their place is a kind of melancholic stasis, a dimly lit existential end-zone where personal items (words, memories, photographs) are examined, and more often than not, found wanting. Works like Andrea, Sick of Goodbyes and Look Out for Hope are blindingly and painfully specific, like more desperate versions of the post-it notes we stick to our fridges, reminding us of what we've done and what we've yet to do.

<< Home