Monday, October 30, 2006

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Cleveland Hopkins International Airport (Display Model View)

Cleveland Hopkins International Airport (Display Model View)From my new favorite piece of inadvertent art, the Shannon Graphics business and industry graphics home page, a virtual world inhabitated primarily by this guy, and these two women.

Highlights include:

Computer Modelled Plant Materials-a kind of extended digital mash-up of Jeff Wall's "Milk" and "Tran Duc Van."

Norfolk International Airport- A John Heartfield like view of a modern airport (note our man in far left of the first image.)

The Hamlet at Jericho N.Y.- Some sort of weird Ed Ruscha/Dan Graham afterlife.

Also not to be missed:

The creepy architectural redundancy of the numerous Church and god-related projects, and the even creepier 'first-person shooter' feel of all those middle schools.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

Friday, October 27, 2006

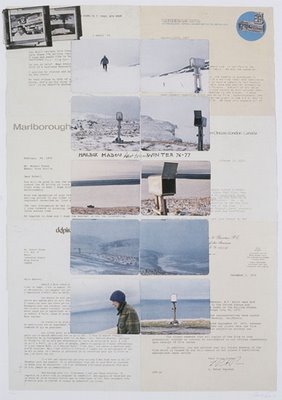

Robert Frank

Robert FrankCollage Suite, 1980.

One of 6.

At the Equinox Gallery until Nov. 25th.

Robert Frank's late work seems to be barely tolerated by a lot of artworld folks, most of whom can't seem to reconcile the visionary milestone that was The Americans with the sloppy, embarrassingly personal films and photo-works that have dominated his output ever since.

The problem, I'm told, is twofold. Not only are the later works hopelessly retrogade in comparison with his earlier groundbreaking photographs (Rauschenberg's silkscreens having already been around for about a decade by the time Frank began cutting, painting and collaging his photographs,) but the undistilled emotionality of much of the work seems too raw, too formless to be able to inspire or sustain much critical examination; as if Frank were tearing individual pages from his diary and tacking them to the wall as art.

The subject of the film and photo-works is invariably Frank's own sense of loss. The loss of his belief in the power of photographic images, and more tangibly, the loss of his two children, Andrea and Pablo, to death and mental illness in their early twenties.

It's pieces like Andrea, 1975, in which Frank states flatly "...she was 21 years old and she lived in this house and I think of Andrea every day." that are often singled out for complaint by his critics as being too nakedly confessional.

"For an artist of public sensibility, the howl of loss needs a ceremonious consistency so that private sorrow may have a public shape..."

-W.S. Di Piero

In other words, all the private pain in the world don't add up to a drop of public art if it isn't first filtered through a recognizably formalized image, (think of those screaming fragmented figures in Guernica, or the swirling, circular unity of The Scream.) In comparison, Frank's collages seem about as fully formed as the inside of a tomato. They are too close to the center of Frank's pain for comfort.

But it's this alarming emotional proximity that accounts for their unique power (and it is unique, as any first-year art student whose tried to imitate Frank's seemingly artless approach to collage will tell you.)

There is something in the work that is simultaneously disconcerting and comforting. The very elements that make Rauschenberg's collages so much fun- the movement, the vibrancy, the swing of them- are consciously and deliberately absent from Frank's images. In their place is a kind of melancholic stasis, a dimly lit existential end-zone where personal items (words, memories, photographs) are examined, and more often than not, found wanting. Works like Andrea, Sick of Goodbyes and Look Out for Hope are blindingly and painfully specific, like more desperate versions of the post-it notes we stick to our fridges, reminding us of what we've done and what we've yet to do.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

When boarding public transit, Victorians say "Hello!" to the bus driver, and when exiting they say "Thank you!". Don't ask me why, it just seems to be the way of things here. It doesn't matter how crowded the bus is or how many people are exiting, when those back doors swing open it's "Thank you! Thank you! THANK you! THANK YOU!" like a line of penguins squawking their way off an iceberg.

When boarding public transit, Victorians say "Hello!" to the bus driver, and when exiting they say "Thank you!". Don't ask me why, it just seems to be the way of things here. It doesn't matter how crowded the bus is or how many people are exiting, when those back doors swing open it's "Thank you! Thank you! THANK you! THANK YOU!" like a line of penguins squawking their way off an iceberg.I'm from Vancouver where we don't say anything to the bus driver, so I find this all a little uncomfortable. The grey faced anonymity of public transit has always appealed to me in a Kafkaesque sort of way, and to be confronted with this flip-side "Ozzie and Harriet" version of it so late in the game is disconcerting. Maybe I just need to give it a bit more time.

I shocked myself by trying out a tentative "Hello" on the bus driver yesterday morning and was reciprocated with a booming "Hello!"in return and approving smiles from the passengers, so it's easy to slide into these things.

"Victoria," says my friend KB, "is a velvet rut."

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Posted on Craigslist:

Posted on Craigslist:CONFUSION PARADING AS ART

"My wife’s annoyingly bohemian niece gave us this piece of abstract "art" after her graduation. She was in art school for almost 6 years and, yes folks, this was part of her senior thesis.

If you're interested in completely useless hanging wire objects that merely consume space and inspire nothing more than smirks from visitors, this piece is for you. Or, if you want to send someone a not-so-subtle message letting them know you hate them, this piece would make the perfect gift.

First person to come to my house to pick this crap up gets it."

Friday, October 20, 2006

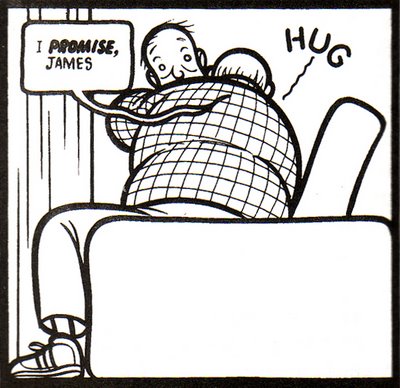

Chris Ware on the two "hugging scenes" in Jimmy Corrigan:

"Well, first of all, I don't think it's necessarily an impotent gesture. I'm not making political statements about hugging. As a younger writer, it's much easier to present a situation where it seems impotent, rather than to present a situation where it seems honest and real. I don't think that right now, with my limited skills, that I could create an embrace which could be incontrovertibly interpreted as an authentic dramatic moment. The Great Embrace, which always seems to end every Hollywood movie after people have narrowly escaped a big explosion--this new thing that they do in movies where they run away from an expanding ball of fire that's following them--they either acquire or manage to save a kid, or two kids, and then they hug tearfully. I just don't know if I could even present it in such a way that it would seem...real."

I had a talk with my pal Jon about this when I was in New York, and he said something along the same lines. That at this point in our culture, it's much easier to show the emptiness of something- the falsity of something- than it is to show something genuine and have it be believed. The former somehow reads as truth, even though it's merely the revealing of a lie, while the latter feels false to us, even though it is often a representation of truths we've seen and felt our entire lives. Sunsets anyone?

Having said that, I just watched the much hyped french-canadian film C.R.A.Z.Y.-- and despite all the annoying neo-scorsese camera work and predictable MTV style editing, it's second to last scene--in which father and son suddenly find themselves embracing--struck me as genuine, believable, and utterly earned.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

What are they putting in the coffee over at Canadian Art Magazine's staff room? Some sort of odourless mental retardant?

Verbatim from the current online edition's front page:

"Much of the success of the painter Shelley Adler’s current exhibition at Nicholas Metivier Gallery is in her treatment of subject matter whether it's an eerie close-up of a young boy sleeping or a candid portrait of a young woman in a towel. But on closer inspection it is the sheer visual power of Adler’s skilfully painted canvases that demand attention. Lushly rendered in the vibrant, hyper-real colours of Pop art, Adler’s thick brush strokes and smooth surfaces read like frosting on a birthday cake that beckons to be touched. The unconventional colour of her canvases evokes definite emotions and also conveys a strong decorative and aesthetic quality. Comparisons with Warhol’s silkscreen portraits are unavoidable. Take for instance High Tension Magenta, a magenta-hued close-up of a beautiful woman’s face that expresses a real sense of anxiety and anticipation with a masterful painterly touch that ultimately privileges surface over meaning. Very different but equally appealing and unnerving are Adler’s paintings of empty banquet tables set for a meal. These scenes are like portraits in absentia where the viewer is left to fill the seats with people then construct a narrative."

Verbatim from the current online edition's front page:

"Much of the success of the painter Shelley Adler’s current exhibition at Nicholas Metivier Gallery is in her treatment of subject matter whether it's an eerie close-up of a young boy sleeping or a candid portrait of a young woman in a towel. But on closer inspection it is the sheer visual power of Adler’s skilfully painted canvases that demand attention. Lushly rendered in the vibrant, hyper-real colours of Pop art, Adler’s thick brush strokes and smooth surfaces read like frosting on a birthday cake that beckons to be touched. The unconventional colour of her canvases evokes definite emotions and also conveys a strong decorative and aesthetic quality. Comparisons with Warhol’s silkscreen portraits are unavoidable. Take for instance High Tension Magenta, a magenta-hued close-up of a beautiful woman’s face that expresses a real sense of anxiety and anticipation with a masterful painterly touch that ultimately privileges surface over meaning. Very different but equally appealing and unnerving are Adler’s paintings of empty banquet tables set for a meal. These scenes are like portraits in absentia where the viewer is left to fill the seats with people then construct a narrative."

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Sunday, October 08, 2006

So far, the job duties at my new place of employment seem to consist of the following:

1:00 pm-6:00 pm - Hurl hardcover copies of Bob Woodward's new book "State of Denial" into the surging crowd on the other side of the register while simultaneously catching and processing the non-stop rain of cash, credit cards and personal insults coming in the other direction.

6:00 pm-10:00 pm - Twiddle thumbs.

1:00 pm-6:00 pm - Hurl hardcover copies of Bob Woodward's new book "State of Denial" into the surging crowd on the other side of the register while simultaneously catching and processing the non-stop rain of cash, credit cards and personal insults coming in the other direction.

6:00 pm-10:00 pm - Twiddle thumbs.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

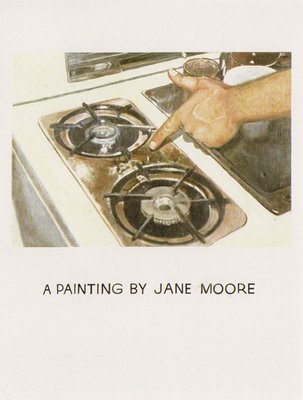

John Baldessari

John BaldessariA Painting by Jane Moore

1969

"These paintings actually happened during my first year at UCSD, and from that time I owe a great deal to David Antin. I really felt like I'd met a person that had similarly crazy ideas as I had, and honestly believed in them. I had great conversations with him. And I remember once, walking from one building to another, we were talking about both of us having a fondness for amateur painters. I said, "You know, I really think some of these painters are pretty good, they're just showing in the wrong venues, and they're painting the wrong subject matter, but as painters, they're really not bad. I honestly have to say that." And then he shared my concern: having just done the works we discussed, those phototext and text paintings, I was in a frame of mind that I didn't need to physically do the paintings. I said I think I want to try to get other painters to do my paintings, because I don't think I have to do them.

So I'd go to county fairs - this art show, that art show. At the time, that was mostly where you saw art in San Diego. The La Jolla Museum of Art was the anomally. Then I began just writing down names. And certain names began to crop up for me, time and time again. the quality of their painting was so consistent. By then I had my little truck and I went around to see if it would work. I went to the first artist and said "For a fee, would you paint a painting on commission for me?" and I explained what I was going to do.

Then I had to find subject matter. I had just finished this other project where I was having a friend of mine, George Nicolaidis, walk around and point out the things in a visual field that jumped out at him. Again, I was exploring the impetus to do art - first you have to choose and select. As he pointed, I would photograph him in the act of documenting that, rather than writing it down. So I had all these slides with a sort of documentary nature to them. They weren't about beautiful composition; I was just recording the fact of something being selected. And so I decided to use those. So to each artist, I would bring about a dozen of those slides, although I had maybe seventy or so of them. And I'd say, "It doesn't matter to me, just choose one to paint."

Sunday, October 01, 2006

"The goddamn septic pump isn't working again."

"The goddamn septic pump isn't working again."A continuing problem over at my current favorite blog, Going Rural (Two artists move from Vancouver, B.C. (pop. 2 million) to Dana, Saskatchewan (population: 30). Can they survive rural life?)

And I thought moving to Powell River was a shock.

I have a hazy memory of Serena as being the girl who worked the front counter at Beau Photo, and of Tyler as being the creator of my favorite piece at the 2003 Emily Carr grad show; a tiny plastic motorcyclist "riding" the grooves of an archaic toy record player that pumped out the same nauseatingly slow loop over and over again: "Head out on the hiiiiiiiiighway, lookin for adveeeeeeenture."

Scroll to the bottom of this page to start from day 1 of their move.